Special girls park

Do you know

Special park

Your smile

make all 100%

happy

That was the only entirely nonsensical thing I saw while I was there, but there were some other interesting translations. A sign that said, “Our bus is carrying out piston operation from the Himeji station southern entrance to this hotel.” One admonishing, “Eating and drinking in this place should withhold.” Instructions for using an intercom that told you to “Release the red button when you hear.” Well, when you want to hear, or, as we would really say it, “Release the red button to listen.”

Japanese doesn’t use articles as English does, and in their translations they often seem to randomly sprinkle definite and indefinite articles, with little regard for usage. At one meal, I ordered something that was translated as “Duck, and the salad of a sweet potato,” expecting to get a main portion of duck, with some rendition of sweet-potato salad on the side. What I got was a salad of mixed greens, dressed with a vinaigrette and topped with a few slices of duck and some diced yellow sweet potato. Good, but not what I expected.

They also appear to use pronouns differently, resulting in some sentences that are entirely lacking in pronouns (the subject has already been established, so they’re not needed). In a description of a historical battle, one sign talked about the army this way: “In a dangerous storm, turned off a light and suppressed a voice and marched for a surprise attack.” It’s an odd sentence, and yet it’s entirely understandable.

Written Japanese uses four scripts — five, if you count the use of Arabic numerals (which is handy: whatever else we can’t read, the numbers, including times and prices, are readable to us). The most complex script is kanji, literally “han characters”. This is the script adopted from Chinese, and it is mostly readable by the Chinese (the characters are spoken differently, so the Chinese can’t understand spoken Japanese, but they can read what’s written). There are a great many ideographic characters, and there’s little hope of reading this without serious study.

There are two kanas, phonetic scripts: hiragana and katakana. It’s not clear to me when they use one as opposed to the other, but each of these has only about 50 phonetic characters, and these are easily learned (I haven’t yet, but I will before my next trip there), allowing one to sound out things that are spelled in the kanas.

I say they’re “phonetic”, but they’re not strictly alphabets: each kana symbol represents a syllable, and each Japanese syllable consists of a lone vowel, or a vowel preceded by one of nine consonants: K, S, T, N, H, M, Y, R, and W. So there are kana symbols for ka, ki, ku, ke, ko, and so on. There are a few variations: si turns into shi instead, for example, and ti becomes chi, tu becomes tsu, and hu becomes fu. There is a syllable-final n, which is said with some form of nasality, depending upon the subsequent syllable and the speaker’s accent.

Four of the consonants can be modified into related ones using diacritical marks: k can become g, s can become z, t can become d, and h can become b or p. Finally, if the -i version of a consonant is followed by ya, yu, or yo, the i sound is dropped and the result is a single syllable. For example, the katakana for “Tokyo” would be トキョ, which is not read as “to-ki-yo”, but as “to-kyo” (but Tokyo is normally written in kanji, as 東京).

The fourth script is romaji, Roman characters — transliteration into English characters. That’s mostly seen as initials and other abbreviations, things like “JAL”, “JR”, and “NHK”. It’s also used to make things readable to foreigners, and there’s enough of that in the transit system, street names, and the like to help one get by. The subway station I used, near my hotel in Tokyo, was 京橋, but it was also labelled Kyōbashi, so I didn’t have to figure out the kanji to know where I was (the station was also numbered, G10 (station 10 on the Ginza line), to make things even easier).

One thing that adds to the image of written Japanese as daunting is that words using these scripts can be intermixed in a single sentence... and Japanese doesn’t use spaces between words, so it all looks like one long string of scribbles.

Because all Japanese syllables end in vowel sounds (except for the syllable-final n), an adjustment has to be made when they adopt a word from another language, such as English. Such words are normally spelled in katakana, and vowel sounds are inserted to make them spellable — and pronouncable — in Japanese. Ice cream comes into Japanese as アイスクリーム, ai-su-ku-rii-mu (and definitely not as the Japanese words for “ice” and “cream”). Some of the loaners are amusing; what we call “french fries” are called フライドポテト, fu-rai-do-po-te-to.

Mostly because of the difficulty in reading Japanese words, I learned essentially no Japanese while I was there, which is disappointing. I arrived armed with three basic words: hai (はい, yes), arigato (ありがと, thank you), and kudasai (ください, please (in some situations)). Not knowing when to use the third properly, I didn’t use it. I sprinkled the other two liberally. And I didn’t really learn any more. That certainly made it clear how important it is to my learning to see a language written, and to be able to read it.

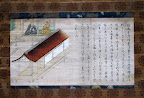

The Japan album in my photos includes a number of examples from the Tokyo National Museum, including the one above left, which I like a lot, and which mixes pictorial art with calligraphy.

3 comments:

>That certainly made it clear how important it is to my learning to see a language written, and to be able to read it.

I would really love to learn sign language. But there was no easy way to write it down when I was taking classes, and so I couldn't study well, and after 4 classes, still knew very little.

With video now being so pervasive now, I imagine the next class I take (who knows when) will be a totally different experience.

Thanks for this post. I have a friend whose love for Japanese and Chinese culture has taught me a lot, but I sure didn't know about the 5 ways of writing.

Hiragana is used for normal writing - the kanji are essentially used for roots and the kana for the grammatical stuff, inflections and so on. Katakana is normally used to the way we use italics and bold - for emphasis, and for writing foreign words, etc. Children begin with kana and learn kanji in batches as they go to school until they've mastered all the required ones. You'll see furigana in their books, the kanji's phonetic transcription in tiny kana above the kanji, as an aid to learning them.

There was an amusing scene in Sailor Moon when the title character, a notoriously bad student, sent herself a letter from the future; her friends were highly entertained to see that even adult Usagi writes in kana, like a schoolchild.

(I'm trying to learn Japanese at the moment. Man, outside the Indo-European fold things get weird!)

«outside the Indo-European fold things get weird!»

That's one thing that particularly fascinates me about languages: how different language families develop very different ways of expressing the same things — all internally consistent, all workable, all able to be learned by children as part of their early childhood development, and yet so very different conceptually.

It shows how many different ways we can devise to communicate.

(Another thing that I find fascinating is what different sounds we use in our languages — and here it's not just between language families, but from language to language within families. People who learn English as children can't generally, as adults, make some of the sounds that native German speakers, native French speakers, native Russian speakers learned to make in their childhoods. Adults who are native Japanese speakers can say "book-u", but can't say "book". Native Spanish speakers can say "eh-study", but can't say "study". Wow.)

Post a Comment